Debating Land Power and Customary Law in Colonial Botswana

By Gerardo Manrique de Lara Ruiz

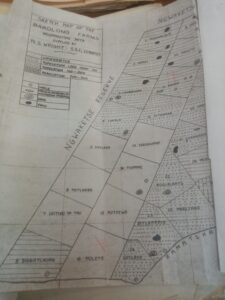

In May and June of this past summer, I traveled to Botswana to explore several archival collections. I visited not only to the National Archives in the capital city, Gaborone, but also to smaller repositories in the border city of Francistown, and the village of Serowe. In Gaborone, I looked for files on cattle and soil erosion to locate potential conflicts between the small settler population and the different African communities of the Bechuanaland Protectorate. The documents I examined suggest that, in the 1930s and 1940s, settlers and colonial administrators used the idea of “land erosion” to deny African communities of more land, instead they suggested the problem was cattle overpopulation. They made development projects conditional on the reduction of herd size limiting African wealth considerably. The extension of loans to farmers was also part of these discussions. African leaders demanded that since most of them had private land and the colonial government actively prevented them from acquiring it, banks should accept cattle as collateral for loans. Their petitions were denied.

I also looked at debates over “custom”. An interesting set of files referred to an unintended consequence of the famous Tshekedi Khama case over the flogging of white men in customary courts: the segregation of the “reserves” along racial lines. Bathoen II, kgosi (“chief”) of the Bangwaketse, argued that “chiefs” had the right to impart justice and punish Europeans “since time immemorial.” There were white blacksmiths living in Batswana towns since the late 19th century, and they had formed mixed-race families. Europeans and their descendants participated in the life of the community and the kgotla (“traditional” court). Their continued presence became a risk for the dikgosi since they ceased to have jurisdiction over them. This prompted a series of discussions on “custom” and the future of mixed-race people in the protectorate. While “assimilation” was a possibility, in the end they were expelled from the community and had to form new settlements. This case exemplifies how debates over “custom” had tangible and unexpected effects over people’s lives beyond the courtroom and political games of succession.

In Serowe, the capital of the Bamangwato community, I visited the archives of the Khama III Memorial Museum. The archivists were very welcoming and had a deep knowledge of the local history. The collection contains many documents donated by the Khama family. This family was instrumental for the establishment of the Protectorate in the 19th century, the sustaind resistance to colonial rule in the 20th century, and the decolonization process. The two most widely recognized figures of the family are Khama III and Sir. Seretse Khama, the first president of Botswana. However, I paid particular attention to the papers of regent Tshekedi Khama. The museum preserves many letters regarding Tshekedi’s multiple lawsuits against the colonial government, his relations with other “chiefs” like Bathoen II, the advisory council, and his interactions with the League of Nations and the United Nations. One of his more interesting international causes was the advocacy for Herero refugees and their potential relocation to a South West Africa independent from South African control. The conflicts over South West Africa extended beyond Herero refugees. Politicians in the Bechuanaland Protectorate also protested the kidnapping and enslavement of Masarwa men by white settlers. The archives contain multiple testimonies of people that escaped South West Africa and hoped to be reunited with their families in the future.