A Journey Through Ghanaian Archives

By Beverly Val-Addo

The narrative of the Atlantic world and its making is vast and complex, often depicted through the lens of great men, monumental events, and overarching cultural shifts. My research focuses on the role Black women played in shaping Atlantic history. It seeks to explore how diasporic women, given their unique experiences in the Americas, can reshape our understanding of the Gold Coast during the nineteenth century. In thinking about the role of gender, I have taken a particular interest in material culture, land, conjugal relationships, and labor in various forms. My coursework during the first year of my graduate training, particularly on Land and Politics in Africa and Latin America, provided a foundation for understanding the meaning of land beyond its economic value. After concluding my first year, I set out with the intent to delve into local archives, where I wished to uncover as much information as possible concerning individuals who might not appear in colonial archives.

Unlocking the Past

In June 2024, I left the United States with aspirations of recovering undigitized sources related to land. After arriving in Accra, Ghana, I would spend most of my time at The Public Records and Administration Division (PRAAD). I spent the first week and a half of this research trip acclimating, familiarizing myself with PRAAD’s manual catalogs, and exploring special collections related to missionaries and abolitionism in the Gold Coast during the nineteenth century. In addition, I delved into British colonial ordinances, correspondence between chiefs and the colonial government, as well as exchanges between the colonial administrations in the Gold Coast and Lagos.

One special collection contained several documents on boundaries and land disputes as well as probate court records. For a week, I rummaged through boxes, looking through several legal cases concerning land disputes. Some of those disputes involved local and diasporic women who made use of the different legal structures in place. While some of those legal cases were well into the twentieth century, they often made references to colonial land ordinances and waves of migration to the Gold Coast dating back to the mid-nineteenth century.

After making these exciting discoveries, I arrived at PRAAD one Wednesday morning around 9:00, when I typically did, to find that the archives were closed. I soon found out that the ministries in Ghana were undergoing a nationwide strike over salary structures, which halted the research process for two weeks. While waiting anxiously to receive news about the government’s negotiations with a trade union, I continued to look through digital repositories provided by Emory and visited the University of Ghana, another local institution in which I could attend scholarly events, inquire about microfilm, and explore the Africana Collection within the Balme Library.

Sources

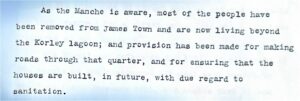

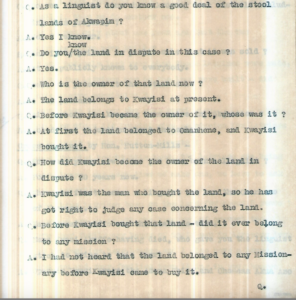

The primary sources that accompany this blog post are a transcript from an 1880s meeting between a Ga king and a colonial administrator concerning land, a 1908 interview concerning public health, as well as a legal record of a land dispute involving a prominent Christian missionary. Following their arrival to the Gold Coast in the nineteenth century, local rulers gave Afro-Brazilians large tracts of land, with women sharing in land ownership. The interview between King Tackie and the administrator touches on how African elite men mobilized against the colonial government and engaged in conversations around land ownership. The 1908 interview highlights the correlation between disease, sanitation, and land dispossession. Finally, the 1929 appeals court record reveals how diasporic women in the early twentieth century initiated land disputes and navigated colonial property laws as well as fraught discussions over their identity and belonging.

Exiting the Archives and the Journey Forward

On my final day in the archives, I could not help but reflect on my entire research trip and thought about the people I encountered at PRAAD. I had the pleasure of meeting scholars from around the world, but I also encountered everyday Ghanaians who were desperately seeking help from archivists. Many of them were engaged in land disputes themselves and were searching for evidence of their family and friends’ ownership of land.

As she was sending me the last of my scanned documents, one of the archivists, who had been instrumental in helping me identify sources, lamented about a document she had just shared with someone across the room. She explained that the document would undermine the person’s arguments for their legal case. The archivist revealed that much of her work at PRAAD revolved around helping everyday people involved in land disputes. The primary sources I have acquired from this research trip will be integral to my dissertation writing and can be valuable beyond the academic sphere. I hope this historical research will, in some way, contribute to ongoing conversations about land and politics in contemporary Ghana.